Probably most of you have been curious about the spelling of our conference venue, Gödöllő. Indeed, the letter ő (and the letter ű) is not used to denote the long ö or ü sounds in any other language of the world. And this is just the beginning. Unless you hear or see some scientific text full of Latin-derived technical terms, you feel completely lost. Not a simple familiar word anywhere! This is also partly the result of the so-called linguistic revival of the early 19th century, since there were many more Latin words in our earlier Hungarian. It was not simply the result of belonging to the Latin Christian culture. (We often felt and feel, and rightly so, that we were and are living on the border between the Latin and Byzantine worlds). But also of the fact that Latin was the 'official language' of the Kingdom of Hungary until the end of 1844. We are, if you like, the most Latin!

Latin was the language of the official administration and the judiciary, except for a brief interlude by the language decree of the Austrian Emperor and King of Hungary Joseph II in 1784. After his death, there was an immediate reversion from German to Latin. Of course, in everyday life (oral and written), the inhabitants of the country, the various nationalities, communicated with each other in the language used locally. Latin thus remained a means of resistance to Germanism and a good means of communication in a multi-ethnic country. The loss of territory and the forced loss of permanent linguistic contact between nationalities after the Treaty of Trianon, then the expulsions of Germans and Slovaks (the latter by population exchange) after the Second World War and the isolation during the communist-socialist period combined to make the knowledge of foreign languages in a linguistically very homogeneous country still rather poor, even today, 35 years after the political changes.

There are certainly some oddities that are shocking even from Hungarians who speak foreign languages on a fairly good standard. If we are tired and not paying enough attention, you may find that we use masculine grammatical forms for women and feminine for men. How can it be? Like some languages, as our distant relative Finnish, we don’t have grammatical gender. We simply don't divide (linguistically) the world into two parts. And what to do with the neutral gender! When translating poetry, we are in particular trouble. Translating 'ő' (he/she/sometimes: it) as masculine or feminine or even neuter is completely misleading. We think in gender-neutral terms. Yes.

It may also be surprising if we use a singular number after two singular subjects, according to our logic. In Hungarian, this is usually the correct way, but it is changing under foreign language influence. (Latin did not impress us in this respect.) It is a matter of temperament and linguistic perception whether we accept or support these changes or not.

Well, and all the different verb tenses! A single past tense is enough for us. We used many more verb tenses until the 19th century, but most of them are now obsolete, understood only from literary texts, and even the more educated are not very good at using them actively in writing. Our old future tense is also extinct, replaced by a circumlocution, but we don't need to use it, because the simple present tense is suitable. Isn't it economical?

On many other peculiarities of our language, almost all of which, of course, have linguistic parallels nearer and further afield, you will enjoy the brilliant writing of linguist, poet and literary translator Ádám Nádasdy. (The earlier published article is published with the author's permission.) The author of these lines was taught by Nádasdy Modern Persian phonetics in Iranian studies at Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest. As a professor of the Department of English Linguistics at the same university, Nádasdy introduced (through his enjoyable lectures) a large number of students to modern linguistics, and his radio programmes, which have been broadcast for decades, have had a nationwide impact. He lives in England and Hungary. (Déri Balázs)

by Ádám Nádasdy, Budapest

You can be proud of anything, if you really want to be proud. Ostriches, I suppose, are proud of not being able to fly – this would be an embarrassment to most birds, but oh how fast an ostrich can run! Hungarians are proud of their language, just because it is so different from all European languages, unable to express things like masculine and feminine, having no word “to have”, but being able to express (with a separate verb conjugation!) whether the object is indefinite or definite. Thus Látok! means “ich sehe (überhaupt, oder etwas unbestimmtes), while Látom! means “ich sehe es”. Hungarian does not belong to the Indo-European [indogermanisch] family: the only other such languages in Europe are Finnish and Estonian (with these Hungarian is distantly related), Basque, Maltese and Turkish.

The Hungarian language is extreme, and so (they say) is the Hungarian temperament. Attractive but unreliable. It accompanies you like a faithful friend, then at one point you turn around and it’s gone, abandoning you to struggle with expressing yourself. Especially if you translate from or into Hungarian. Nothing is the same. “Musik” is zene or muzsika, and the two have different connotations. “Ich habe Fieber” is Lázam van, that is, “Fieber-mein ist”. The exchange “Ist der Artzt weggegangen? – Ja” would be Elment az orvos? – El, that is, “Wegging der Artzt? – Weg.” Nowadays nobody would seriously connect language with national character, but this was widely done in the Romantic period and after, all through the 19th century. The Hungarians realized they were “alone”: when all other nations established their linguistic family ties, Slavic, Germanic, Celtic and so on, Hungarians found no ties. Then scholars discovered around 1800 that the relatives of Hungarian were Finnish, Lappish, plus some little-known languages in Siberia. And they were very distant relatives, not like German and Danish, or French and Italian, where the relations are easy to see. This was received with disbelief and disappointment, since people had expected something more spectacular: for another hundred years amateur (and not-so-amateur) linguists were busy proving that Hungarian was related to Turkish, Japanese, Hebrew, Sumerian, or what you will.

Not all Hungarians are happy with this language: some can never learn it, either because they go away early or they come here late. Franz Liszt was proud of being Hungarian, but didn’t speak the language because he came from a German-speaking family and spent most of his life outside Hungary. My grandfather, Eduard Ritter von Hübner, was born in Prague in 1883 and came to Hungary in 1920, but comfortably managed here with very little Hungarian till well into the 60s, when the last generation of German-speakers began to disappear. I remember the national census of 1960. Since Opa didn’t understand the questions, I filled in the questionnaire for him, translating into Hungarian: Geburtsort, Beruf, till it came to “Anyanyelve” on the sheet. “Muttersprache?” said I. “Ungarisch”, said he, in German, of course. “Aber Opa, du kannst ja garnicht Ungarisch,” I protested, preparing to write “német” (= deutsch) into the rubric. I was thirteen. “Dummes Kind!” he shouted, “was weisst du vom Leben? Schreib “magyar” und halt’s Maul.”

Hungarian, in one way or another, has always been a minority language. First, when its earliest speakers, the Magyars split off from the Finno-Ugric language area (east of the Ural mountains) around 1000 BC, and joined the alliance of semi-independent Turkish tribes in southern Russia, who all spoke Turkic languages like Chuvash, Bashkir or Tartar. The Magyars, for some mysterious reason, did not abandon their Finno-Ugric mother tongue, even though they must have been bilingual (Hungarian–Turkish), as is shown by plenty of loan-words from Ancient Turkish, including basic ones like kék ‘blue’, gyárt ‘to manufacture’, and even baszik ‘to fuck’. Their names (e.g. Árpád, Gyula for men, Emese, Sarolt for women) were also Turkish, as were their clothes, weapons, kitchen utensils and burial rites. Thus it not surprising that the Byzantine chronicles which first mention the Hungarians (around 950 AD), call them “Turks”. Actually, the Hungarians themselves had lost all memory of their Finno-Ugric origins. They thought they were a far-off branch of the Turks and/or Mongolians, and that ultimately they derived from the Huns. For many centuries this was the accepted theory taught in schools and, even after being ousted from serious scholarship by the Finno-Ugric discovery, it survived as a neo-romantic and neo-nationalist legend, so much so that “Attila” is now one of the most frequent Christian names among Hungarian men. Other nations look at us in puzzlement: how can you name a little boy after the scourge of God?

In 896, the Hungarians settled in their present homeland, the Carpathian Basin (later organized into the Kingdom of Hungary, which existed until 1920), but they never became numerous enough to fill it: there were large numbers of Slavs, later also Rumanians and Germans living there. True, the Hungarians were the largest single group in the area, but there were always more non-Hungarians than Hungarians living in historical Hungary. Many words were adopted from Slav (asztal “table”, szabad “free”), from Latin (templom “church”, pásztor “shepherd”, sors “Schicksal”), and even Italian (piac “market” from piazza, pojáca “clown” from pagliaccio).

Naturally, the language which was felt to endanger Hungarian most was German: cities were mostly German-speaking, as was printing, correspondence, or theatres, also reinforced by the Habsburg administration. All educated Hungarians spoke German, and those who wrote in Hungarian constantly felt the attraction to import “Germanisms” and at the same time to avoid them. This is why, paradoxically, Hungarian is very similar to German. I am not only thinking of the many German loan-words that Hungarian has adopted, such as példa ‘Beispiel’ from Bild, sógor from Schwager, krumpli ‘potato’ from Grundbirn(e), nímand “insignificant person” from niemand, verkli ‘hurdygurdy’ from Werkel (“musical instrument with a mechanism”). Much more importantly, it is the common stock of turns of speech [Wendungen] (“mirror translations”) that have made Hungarian similar to German, just like a dolphin is similar to a fish, even though its origin and internal structure is quite different. In both Hungarian and German one can say that someone schneidet auf (= felvág) mit seinen neuen Schuhen, or that he is eingebildet (= beképzelt). The words, the endings, the sounds are different, yet the discourse is parallel. Once in Berlin I read in the paper about some political event: “wie sich das der kleine Moritz vorstellt”. I grinned: this is exactly what we say in Hungarian (ahogy azt a Móricka elképzeli).

After World War I new borders were drawn and present-day Hungary was formed, where for the first time Hungarian was an absolute majority language (Hungary is now about 98% Hungarian-speaking). In the newly formed neighbour states, on the other hand, Hungarians found themselves in a very pronouncedly minority situation. There are roughly 13 million Hungarian speakers, about 75 % living in Hungary and 25 % in the neighbouring countries. This should explain why the language is such an important, even hallowed, symbol of cultural and national identity. When speaking of “Hungarian literature”, for example, one constantly hovers between meaning literature in Hungary or literature written in the Hungarian language. Incidentally, the language itself has always shown little variation: there are only negligible dialectal differences. Hungarian speakers – and literature (or literatures?) produced by them – display few differences from Bratislava through Budapest to Brasov.

The ingrained minority feeling has had interesting effects even in Hungary, where it no longer has any justification: for example, as late as the 1960s actors felt obliged to “Hungarianize” [verungarischen?] their non-Hungarian-sounding names. This has now changed, and we have actors proudly bearing the names Hirtling, Kolovratnik or Papadimitriu. But the feeling that the language has to be defended like a rare plant remains. Purists – some of them too radical, others more tactful and considerate – continue to grumble against the influx of foreignisms, except that the great influencer is no longer German but English. (A couple of years ago some voices even required a law to forbid using foreignisms in public, but thank God it was realized by decision-makers that this is would not bring the required results.) Not only do technical terms like szkenner (scanner) or lízing (leasing) come in, but many words related to current lifestyle and sensibility, such as mainstream, fíling (feeling), retró (nostalgic revival) or badis (someone into bodybuilding, i.e. well worked-out, muscular).

Hungarian is not only different because of its word-stock. Its structure, as the standard technical term goes, is agglutinative. This means that endings are attached to words in a neat and prescribed order, and words can grow to stunning lengths. There are no prepositions, and very few auxiliary verbs. For example, hajthatatlanságunktól means “von unserer Unbeugsamkeit”, and is structured hajt-hat-atlan-ság-unk-tól, each element in turn expressing the verb, the possibility, the negativity, the possession, the preposition (“bend-can-not-ours-for”). And all this happens very regularly, indeed mechanically. Every noun has to have -k as its plural, without exception, even if it is new or foreign, thus les Tuileries becomes a Tuileriák. Even verbs end in -k in the plural (in the “wir-ihr-sie” forms). However, the vowels of the endings will change (“harmonize”) in accordance with the stem. If, in the above long example, the stem is sért “verletzen”, the word will be sérthetetlenségünktõl “von unserer Unverletzbarkeit”, with all the vowels harmonically changing to suit the stem. (This is a phenomenon also found in Turkish.)

As we have said, there is no grammatical gender, thus no difference between “er” and “sie”, “seine Augen” and “ihre Augen”. This makes it possible for writers (and especially poets) to express things in a more abstract or more unspecified way, while in translation it often becomes a problem things in other languages the gender has to be specified, and it is the translator’s responsibility to decide how and when to do so. There is only one past tense, thus no difference between “lernte, hat gelernt, hatte gelernt”. On the other hand, a single word expresses whether the possession or the owner is singular or plural: háza “sein (oder ihr!) Haus”, házuk “ihr Haus”, házai “seine Haeuser”, házaik “ihre Haeuser”.

Hungarian poetry can use very old-fashioned, even classical metrical schemes, because all vowels exist in long or short form: the long vowels are shown in spelling by acute accents (as in Czech), thus á, í, and even ő, ű (the famous double accent or “Hungarian Umlaut”, the horror of all computer fonts). Thus tör is “brechen” but tőr is “Dolch”. This play of long and short makes it possible to write perfect hexameters, and many twentieth-century poets have done so, producing good contemporary poems. Rhyming is also surprisingly popular, and not only for humorous or satirical purposes (as in most Western poetry today), but for serious matters too. The fact that poetry is much more dependent on (and is more nurtured by) the idiosyncrasies of its language may explain why poetry is still said to be the strongest branch of Hungarian literature: obviously such a language, like an unusual block of marble for the sculptor, inspires the poets. But it may also explain why Hungarian poetry is so hard to translate, and why Hungarian prose (which, admittedly, also has its masterpieces) is much more widely acclaimed with the non-Hungarian-reading public.

For Hungarian may be a golden cage for its speakers. It is worth considering the recent history of Hungarian and its speakers with the Irish and their language. Around the middle of the 19th century the Irish (so to speak) agreed among themselves to abandon the traditional Gaelic Irish language and to go over to English. Today almost all Irish people living in the world are native speakers of English, and can no longer read or understand Irish. This may be a sad fact for the loss of a rich and ancient language, but – let’s be frank – a great bonus for the nation, since they possess an international language, and hundreds of millions can easily read anything written by Irish writers (not speaking of the advantages in commercial, military, etc. life). Hungarian was in a very similar situation vis-à-vis German as Irish was with English; however, the opposite happened. in the mid-nineteenth century most people in Hungary, whatever their mother tongue, agreed to switch over to Hungarian, and indeed, in a few generations almost the whole country (certainly what was to become present-day Hungary) became monolingual Hungarian-speaking. Hungarian has become a full-fledged European language, with science, law, business, leisure, crime and literature all being conducted in Hungarian. Open (perhaps too open, some would say) to foreign influence, it shows no signs of decay or destabilization. But when Hungarians cross the border to Vienna, Paris, London, or the non-Hungarian-speaking areas of the neighbouring countries, they are lost, unless with years of hard work they learn a foreign language, by definition very different from theirs. The knowledge of foreign languages is pathetically low, compared to Holland, Portugal, Greece, or Finland. The Irish have eaten their cake; the Hungarians have it.

Little geography of Hungary

Most of today's Hungary is plain, the Little (Kisalföld) and Great Hungarian Plain (Alföld/Magyar Alföld, Nagyalföld), with small hills and elevations barely dividing the lowland landscape. The western border region (the Alpokalja, "feet of the Alps") and Southern Transdanubia (west of the Danube, below Lake Balaton) are hilly. All the Hungarian mountains belong to the category of Mittelgebirge (German term used to describe this characteristic type of low mountain range in Central Europe), as the highest peak in Hungary, in the Mátra Mountain, is also only 1014 metres high. Quite a few prominences are traditionally called mountains, which in other countries would hardly be called hills.

See: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1e/Hungary-geographic_map-en.svg

Except for the 4th Cantus Planus meeting (1990) in Pécs which is located at the foot of the Mecsek Mountain (in Southern Transdanubia), and the 7th conference (1995) in Sopron, at the Sopron Hills in Alpokalja, all the other Cantus Planus meetings in Hungary have been held in towns of the Hungarian Mittelgebirge.

The western part of the Hungarian Mittelgebirge is the Transdanubian Mountains (in Northern Transdanubia), streching from Lake Balaton through the Bakony, Vértes, Gerecse, Budai Mountains east-northeast almost to the Danube Bend, till the Pilis Mountains (north of Budapest), separating the Little and Great Hungarian Plain. Veszprém, the town of the queens in the Middle Ages, in the Bakony Mountains, hosted our 1st conference (1984). After Bologna (1987), the 3rd meeting (1988) took place in Tihany, on the peninsula of the so-called Balaton Plateau, on the north shore of Lake Balaton. Part of the 9th meeting (1998) was held in Esztergom, at the foot of the Pilis Mountains, at the Primate's See of the Hungarian Catholic Church, while Budapest hosted the IMS conference in the framework of which the 10th meeting (2000) in Visegrád has been realised. Although the main venue was the Liszt Ferenc University of Music (Liszt Ferenc Academy of Music) on the Pest side of the capital, the Buda Hills belong to the Transdanubian Mountains on the Buda side.

Barely separated from the Pilis, the Visegrad Mountains are geologically (as of volcanic origine) part of the Northern Mittelgebirge which belongs to the inner volcanic belt of the Northwestern Carpathians. This range stretches from the Danube across Northern Hungary to Eastern Slovakia (Slovak: Matransko-slanská oblast). Its main parts are the Visegrád Mountains, on the inner side of the Danube Bend, and on the other side Börzsöny, Cserhát (and Gödöllő Hills), Mátra, Bükk, and other mountains as far as Prešov (Hungarian: Eperjes) in Slovakia. These long, mountainous and hilly landscapes have been and still are home to other Cantus Planus conferences in Hungary. The historic town of Eger, the south-western gateway to the Bükk Mountains (see below), hosted the 6th meeting (1993) of Cantus Planus.The unique Altar of Yesse in the Roman Catholic Church of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Gyöngyöspata was a memorable highlight of the former excursion. (See https://www.gyongyos-matra.hu/en/sights-en/churches/kisboldogasszony-templom-gyongyospata/) Miskolc, a large city on the eastern side of the Bükk Mountains, with Lillafüred as part of the municipality, was the venue of the 12th meeting (2004). Three conferences were organised in the Visegrád Mountains, at the other end of the Northern Mittelgebirge. One of the venues for the 9th meeting (besides Esztergom) was the small town of Visegrád, namely the Castle Hill (Várhegy), just like the 10th meeting (2000), which was linked to the IMS conference. The 14th meeting (2009) was held at the highest peak of the Visegrád Mountains, in the Dobogőkő resort.

It is high time to show our guests also the central part of the northern mountains. On Friday (Aug. 2), we will take a bus tour around the Börzsöny Mountains and visit a Romanesque village church at one point. In the Cserhát Mountains, a the lower, non-volcanic mountain (or higher hill) region between the Börzsöny and the Mátra, the tiny villages have also preserved many medieval churches despite the general destruction during the Turkish period. The main settlement in the valley between the Cserhát and the Mátra is Pásztó. This is important not only because of its exceptional medieval monuments, but also because it was here that one of the founders of Cantus Planus, Benjamin Rajeczky OCist, born in Eger, lived and worked for a significant part of his long life.

In geological terms, the Gödöllő Hills (Gödöllői-dombság) are considered to be a continuation of the Cserhát Mountains, which is deeply penetrated, becoming increasingly flattened (Gödöllői-Irsai/Ceglédberceli-dombvidék), into the Great Hungarian Plain.

It is a mere coincidence that the local organisers of the Conference are all linked to the settlements of these hills. Balázs Déri spent his childhood in the Tápió Valley, a typical ethnographic area of this region. The faithful of the Catholic villages used to make annual pilgrimages in traditional clothes to Máriabesnyő, which is now part of the municipality of Gödöllő. Moving closer to Budapest, he also stayed with his family in this area in his youth, but, now living in Budapest, he still visits his parents' house every week. Zsuzsa Czagány lives with her family just in the neighbouring small town. Together with her husband, the late Gábor Kiss, they moved here from another neighbouring village, which is another neighbour of Gödöllő. Gödöllő became the residence of Péter Piusz Balogh OPraem, the present abbot, and the family of Miklós István Földváry also settled in Gödöllő.

As described in the Transport & Travel section of the website, passengers from Keleti (Eastern) Railway Station arrive at Gödöllő by fast ("Interregio") train terminating in Gyöngyös or Eger, which does not stop before Gödöllő. Let's make a note: fast trains going further afield, to Miskolc or to Kassa (Slovak: Košice) in Slovakia, do not stop at Gödöllő! The railway line between Budapest and Miskolc is one of Hungary's most heavily-contained railway lines, running along the bottom of the mountains. Branch lines branch off to the left in the valleys between and towards these mountains. Two lines branches off towards the Cserhát at Aszód (which we will probably visit at the end of our excursion) and Hatvan, then others at Vámosgyörk towards Gyöngyös, the gateway to the Mátra Mountains, and then at Füzesabony to Eger. (To the right, the branch lines branch off towards the Great Hungarian Plain.)

Below, we recommend these two latter destinations, which are quickly and conveniently accessible by rail, for those who can extend their stay by a day before or after the conference.

Gyöngyös

Gyöngyös (Hungarian pronunciation: [ˈɟøɲɟøʃ]) is the second largest town in Heves County (after Eger), 60km east of Gödöllő, with less than 30 000 inhabitants. The town lies at the foot of the Mátra, with numerous vineyards. The Baroque and Art Nouveau buildings around the main square were rebuilt after the catastrophic fire of 1917. The winegrowers of the Mátra Wine Region, also known as the Hungarian Tuscany, visit Gyöngyös' main square for the Mátra Wine Days in early summer:

The treasury of St Bartholomew's Church houses Hungary's second largest collection of Catholic ecclesiastical items (after the Esztergom Cathedral):

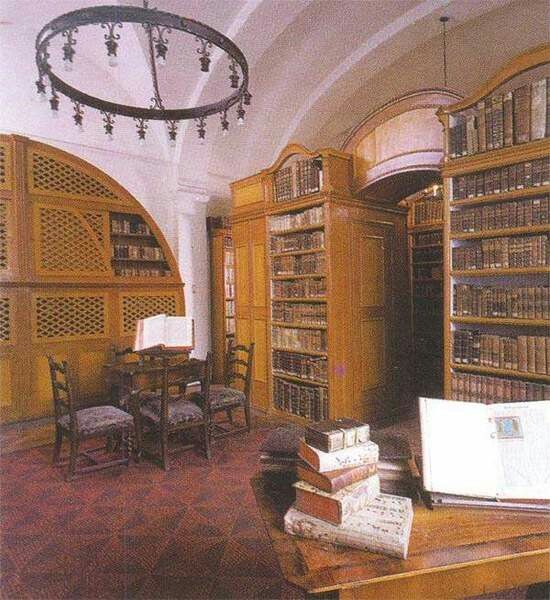

The Church of the Visitation and Franciscan monastery houses the country's only intact and complete medieval Franciscan monastic library.

Very few members of the once-populous Jewish community survived the Shoah, but a small community is still active today. The former basilica-style Grand Synagogue (1930), then a warehouse, later a department store, became a municipal gallery in 2014. It serves community-cultural functions:

The Kékes Étterem (Restaurant) on the main square has a very good reputation.

Menu: http://www.kekesetterem.hu/index.php/etlap/eloetelek-levesek-3

The first train (Interregio) departs from Gödöllő to Gyöngyös at 4:38 in the morning, and from 5:56 every hour until 10:56 in the evening, arriving in Gyöngyös in 57 minutes. The return journey is the same (from 4:08 to 21:08, this last train with transfer, and to 22:18).

Eger, a historic town (more than 50 000 inhabitants) on the hills between the Mátra and Bükk mountains, is located 106 kilometres by train from Gödöllő. Its main attraction is the castle of Eger, famous for the heroic defence of the people of Eger against the Turkish invasion. (A minaret also preserves the memory of the Turkish conquest.)

A day trip to the archbishop's seat includes a visit to the classicist cathedral basilica, several beautiful baroque churches, including the marvelous St. Nicholas Serbian Orthodox church (rác templom, görögkeleti szerb templom),

residential houses and squares, as well as a good wine tasting.

The trains (Interregio) depart every hour from Gödöllő from 5:27 in the morning until 9:27 in the evening, arriving in Eger in 1 hour 21 minutes. The return journey is the same (from 5:02 to 20:08).

Tourist information here.